�Where drum samples are often already fully processed and ready to use, a live recorded drum kit is not.�

A good drum sound almost always stands or falls with the recording. Are the microphones in phase, how does the room sound, are the drums tuned and so on and so on.�

A typical drum multitrack recording will look like this:�

� Kick (possibly divided into a kick in (microphone on the inside of the skin), a kick out (a microphone on the outside of the skin))�

� Snare (possibly divided into a snare top (microphone aimed at the top) and a snare bottom (microphone aimed at the bottom)�

� Hi hat�

� Two overhead microphones�

� Two room microphones�

Optional:�

� Individual microphones for each tom�

� Trash microphone (a single microphone to capture the entire kit)�

Phase:�

Because a live drum recording consists of many instruments all reaching the microphones at different times, there is a chance that some tracks will be out of phase with each other. This means that (part of) the sound will be lost if everything is summed to mono.�

Go back and forth, switching between mono and stereo. If part of the sound drops out, the microphones are out of phase. Move one of the tracks just a little bit at a time until the recording sounds ‘fatter’ instead of thinner.�

Do this with the snare top and snare bottom, the kick in and the kick out, the overheads, the room mics and then the overheads and room mics with the snare.�

Gate:�

Drum mics almost always suffer from bleed, where sound from other drums �bleeds� into the microphone. You can remedy this by using a gate. This helps enormously with kick and snare tracks. Adjust the gate until you hear only the drums you want to hear. Adjust the attack so you can hear the drum �pop’ nicely and adjust the release so that the drums have time to ring out.�

Since toms are often used sporadically you will usually cut out anything except for the tom hits. In order to eradicate bleed entirely.�

EQ:�

Remove or reduce the unwanted frequencies. With the kick, snare and toms, it is often the low mids that make it a bit ‘boxy’. With the overheads and the room mics, these are usually the low frequencies.�

Boost frequencies to bring out the character of the drums:�

Kick: Usually lows and low mids for extra power and high mids for the beater’s snap.�

Snare: low mids for a fat sound, high mids for the ‘crack’ of the snare.�

Toms: lows for the floor toms, low mids for the rack toms, high mids for the snap.�

Overheads: low mids to add some ‘meat’ to the cymbals, high mids for extra presence, highs for ‘air’.�

Compression:�

Drum compression is a separate topic in itself, but broadly speaking you use the compressor not only to adjust the dynamics, but also to shape the transient of a drum sound.�

In general, you use a fast attack to control the transient for a cleaner sound. But if you set it too fast, you’ll squeeze all the life out of your drum kit and push it further back in the mix. Use a slower attack to emphasize the transient of, for example, a kick or a snare drum.�

Set the release so that the drums have time to “breathe” before the next hit.�

Reverb:�

Drums are often sent to a reverb on an aux track. The type of reverb depends on the track, of course. The length of the reverb however depends on the tempo. Try setting the decay time of the reverb tail on your snare so that it is gone before the next snare hit.�

Bus compression:�

To make your drum kit sound like one instrument, send the entire drum kit through a glue compressor with a low 2:1 ratio, a slow attack, and set the release to match the tempo of your track. Make sure that your compressor does not react too strongly to the low end of the kick drum. If your compressor has a sidechain function, use it so that the compressor reacts less violently to low frequencies.�

Saturation and distortion:�

At this point your drum kit should sound clean and even. You can always take them a little more over the edge by adding some (parallel) distortion or overdrive.�

Automation:�

The icing on the cake. Bring your drum kit to life by looking at where and when in the track specific elements of your drum kit need more or less attention.�

Always listen in context of the mix and remember that these are only guidelines. Listen carefully to the arrangement and drums and don’t be afraid to get creative.�

To learn more about music production and how to improve the process of developing, creating and refining recorded music, visit our knowledge base page Music Production Education.

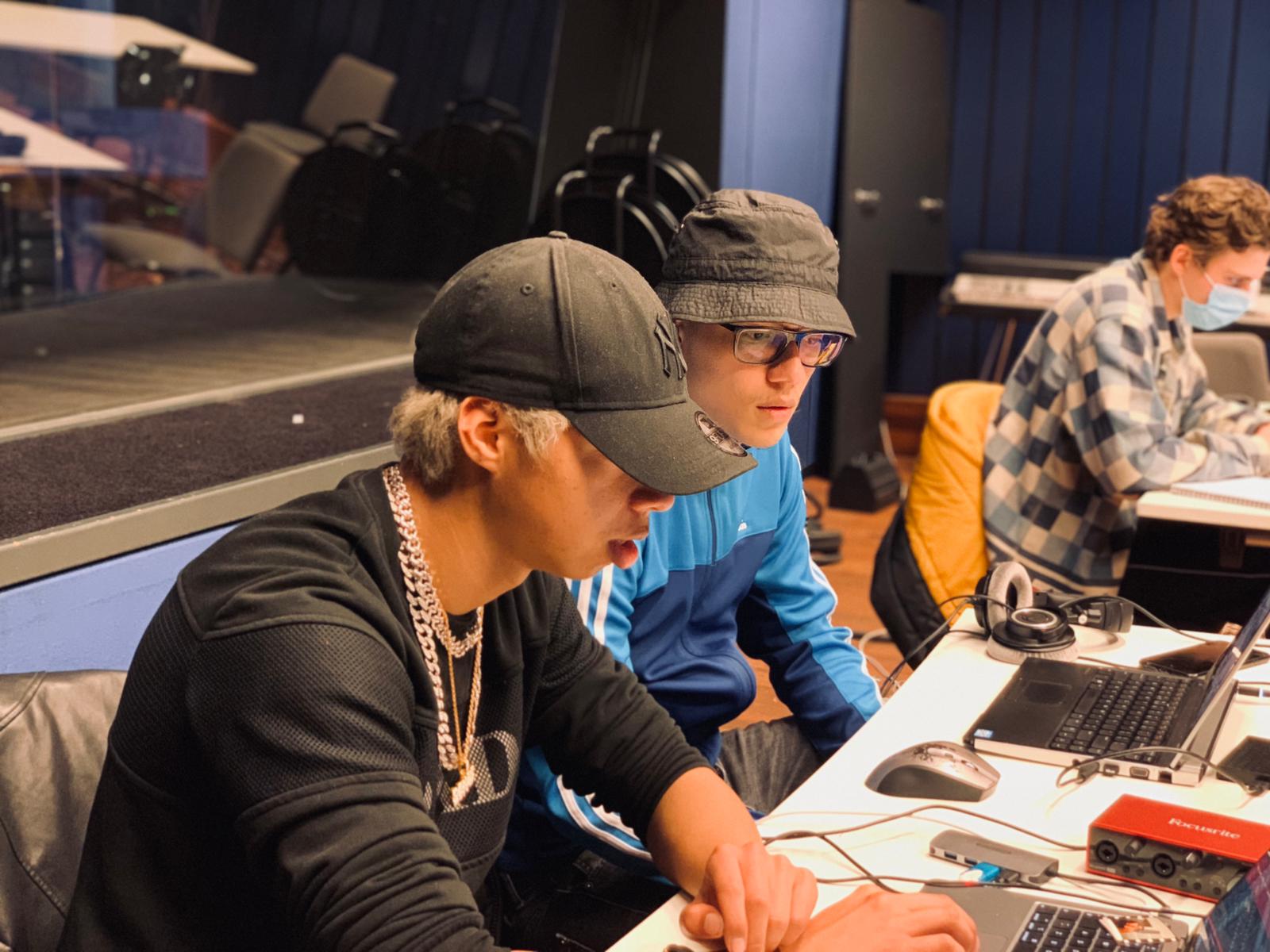

At the Wisseloord Academy you will be prepared for the real thing. You will regularly work on assignments and briefings out of the work field. It gives you a double chance: you can gain experience while making the assignment and if you carry out the briefing well, it may just be that your work makes the ‘cut’. But how do such briefings work and what should you pay attention to when you start working on them?

At the Wisseloord Academy you will be prepared for the real thing. You will regularly work on assignments and briefings out of the work field. It gives you a double chance: you can gain experience while making the assignment and if you carry out the briefing well, it may just be that your work makes the ‘cut’. But how do such briefings work and what should you pay attention to when you start working on them?